It’s not often I refer to suggestions for further reading, but I am now on the lookout for a copy of the article Dorothy Parker, Not What You Expected by Wyatt Cooper (published 1968 in the Esquire). Because reading the 1944 edition of The Portable Dorothy Parker was not what I expected, at all. Despite having read and loved it in my early twenties.

It’s not often I refer to suggestions for further reading, but I am now on the lookout for a copy of the article Dorothy Parker, Not What You Expected by Wyatt Cooper (published 1968 in the Esquire). Because reading the 1944 edition of The Portable Dorothy Parker was not what I expected, at all. Despite having read and loved it in my early twenties.

This was a real treat (so my thanks to the inaccuracy of the Goodreads list of popular books of 1944 which resulted in my jettisoning first and second choices and resorting to re-reading Mrs Parker). All the memorable favourites – in the form of her caustic one-liners and humorous, light verse – were there. The poems bemoaning the pain of love lived and lost in which the men are all bounders and cads with the odd exception far too dull to have a relationship with. (See the perennial attraction of the bad lads.) Lots to smile and nod in recognition at. Because we’ve all been there – and I certainly was in my early twenties. But also lots of yearning for death. Parker’s life story with multiple failed suicide attempts belying my notion that these poems were a play on romantic notions of the grave. No, it was bitter experience, and Dorothy Parker put her own spin and wit to it.

Résumé

Razors pain you;

Rivers are damp;

Acids stain you;

And drugs cause cramp;

Guns aren’t lawful;

Nooses give;

Gas smells awful;

You might as well live.

Parker may have transformed her anything-but-breezy experiences into pithy, entertaining verses, but her short stories poke their fingers right into the ribs of frequently uncomfortable issues. It was the seriousness and the truthfulness beneath their frothy surfaces that surprised me: latent racism in Arrangement in Black and White, the hypocrisy of the rich in The Wonderful Old Gentleman, self-satisfied smugness of the secure and privileged in Mr Durant and The Custard Heart; an excoriating projection of where Parker’s own life-style was leading her in Big Blonde, the story that won the 1929 O Henry award. There’s no moralising in Parker, just a peeling back of the layers as the characters expose themselves by their own actions and words.

While rooted in the society of Parker’s lifetime, many of the dialogues and soliloquies are timeless. (Maybe not the phrasing, but the sentiment.) I defy anyone to read The Sexes and not recognise that these differences still apply. (Political correctness notwithstanding.) Or the trials of a long-term marriage in Too Bad. Or the sorrow when a marriage has ended in Sentiment. I say that but younger generations of womanhood most likely will disagree. Would they sit around for hours waiting for a telephone call from their beau? (The Telephone Call) Or even suffer from wedding night nerves? (Here We Are) Or have a nervous breakdown if they found themselves in trouble? (New York to Detroit) If so, probably more exception than rule these days.

The Portable Dorothy Parker was compiled by Parker herself for The Viking Press to release in 1944 as an inexpensive, portable paperback for service personnel. So it is mostly a compilation of her best work from the previous decades. However, there are a few pieces set during wartime, and Parker choose to bookend the collection with a couple of these. The opening story, The Lovely Leave, tells of the fraught reunion of a married couple during the a one-day leave. The final poem, Warsong, written in 1944, is that of the woman left at home. The poignancy of the final stanza speaks for itself.

War Song

Soldier, in a curious land

All across a swaying sea,

Take her smile and lift her hand —

Have no guilt of me.Soldier, when were soldiers true?

If she’s kind and sweet and gay,

Use the wish I send to you —

Lie not lone til day!Only, for the nights that were,

Soldier, and the dawns that came,

When in my sleep you turn to her

Call her by my name.

In her later years, Parker was to decry her verse as “no damn good”, and admittedly they are not the greatest. BUT they are loved, and they have endured. The Portable Dorothy Parker is the only portable besides The Portable Bible and The Portable Shakespeare that has remained in print since 1944.

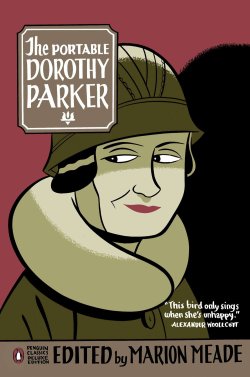

A Note on My Edition

The beautiful deckle-edged Penquin Deluxe Edition, edited by Parker’s biographer, Marion Meade, includes the original Portable plus an additional 270 pages of other writings: stories and poems Parker did not include in her 1944 selection, reviews and personal correspondence. I’ll be taking my time reading these because Parker is one to savour.

The 1944 Club is hosted by Karen at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Simon at Stuck In A Book.

What a great idea – to read a sampler for the event. Dorothy Parker is someone I’ve only enjoyed in short snippets, but I would definitely like to explore some more of her work, more methodically. Enjoy the rest of your volume!

I have a Penguin MC edition, and it always cheers me up when I dip into it

I haven’t read any Parker but she is always in books of quotations. I liked résumé so much when I first came across it that I made the point of memorising it.

Oooh lovely – I’m so glad someone’s reviewed this! I have the old Penguin version but now I’m coveting that lovely American edition with the extra bits. I think I probably missed the serious undercurrents when I first read her in my teens, but I can certainly see them now!

My old Penguin editon fell to pieces ….