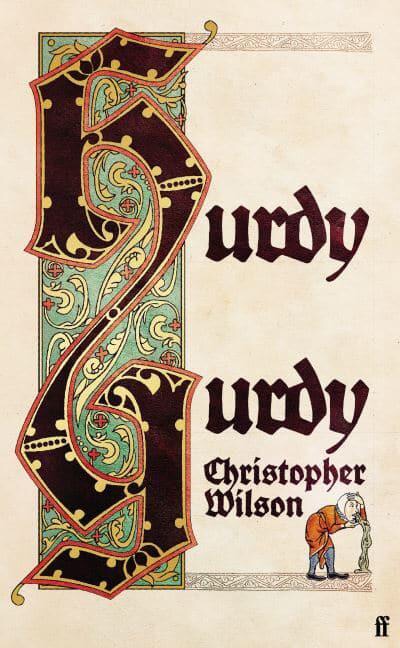

I’d never heard of a hurdy gurdy until I came across The Hurdy Gurdy Man in Wilhelm Müller’s/Franz Schubert’s Winter’s Journey. It has to be said that their hurdy gurdy man is sad devastated creature. The novice friar, Brother Diggory, the hurdy gurdy player, in Christopher Wilson’s has a much more cheerful temperament, but there is an awful lot of devastation coming his way. Not that he’s to be blamed for any of it, is he?

The year is 1349 and it is the season of the plague. Brother Diggory, 16, has lived in the Monastery of the Order of Saint Odo since he was eight years old. The plague has arrived on British shores and is creeping towards the monastery. The abbot assigns Brother Diggory to Brother Fulcro’s medical team. Understanding the coming dangers, Brother Fulcro demonstrates their PPE.

He has a head like a giant crow’s, black with a long pointed beak, and two glistening, black, button eyes. “This will be our protection ….Together with leather gloves and a waxed cape. The miasma will not be able to penetrate.” He shows me the inside of the mask, with the dark glass eyes, and the beak packed with straw, mixed with herbs, impregnated with essences.”

However, Diggory becomes one of the first plague victims in the monastery and is quarantined (read left to die in a boarded up room) when delirious. Against the odds he makes a miraculous recovery, but finds there is no-one on the other side of the door to let him out. Summoning the strength to break out, he is greeted with a scene of horror. His only recourse is to leave the monastery in search of a new future.

He travels north, meets many new folk, malign as well as benign. During his picaresque adventures, he experiences “the hurly-burly, hoopla and hullabaloo of this life”. He swaps the female succubus that was tormenting him in the monastery for real womanly flesh and blood. The trouble is the plague always catches up with him after 2 or 3 days, resulting in death for those now within his orbit. Diggory can’t work it out, but we can, the clues are woven into his observations. Following a second close shave with death, Diggory decides its time to head back south. Perhaps a return through lands already devastated by the plague will stop it from following and persecuting him …

It’s not that Diggory is an uneducated man. For his time he was well-educated, strong in theological thought, stronger and more dangerous still in medieval medical quackery. Wilson has obviously researched this well and thoroughly enjoyed creating Diggory’s earthy, unsentimental and naïve voice in a world full of medieval limitation. Capitalising on the delight for obscure revelation and prophecy, Diggory frequently makes reference to Saint Odo’s The Great Unhappened – a description of the many perils and plagues that would befall the coming generations. These include

the disease of the thinking engines … And as they grew from child to adult, the machines grew cleverer and more memorious. Until they could think faster even than people, and knew more. so before long, people grew lazy, relying on those engines to think for folk and do their work.

Is this a clever trick to allow the medieval characters to return the satiric gaze on those who are reading the satire about them?

Hindsight is such wonderful thing. Which leaves me wondering how we’ll feel about current circumstances in 5 or 10 years time. I do hope though that in the near (?) future, when the pubs reopen, we don’t experience them exactly as Diggory did. 😳

The inn is crowded. And I had forgotten how strong a herd of folk can smell in their plurality – of warm, damp armpits, excrement, rotten teeth, mildewed clothes, woodsmoke, simmering pottage, and stale spilled ale. There is a smoky fug and a clamour of shouting, laughter, singing, fiddle and drum.

Hurdy Gurdy is published by Faber and Faber, established in London in 1929. Since then, they have established a stellar literary reputation and a list which includes 13 Nobel Laureates and six Booker-prize winners. How? Read their history here. It’s fascinating.

Sounds good and this one was already on my long list of TBR.

I read James Meek’s excellent To Calais, in Ordinary Time, which is also set in England in 1349, so it will be interesting to compare approaches.

And Minette Walters has two novels set in 1348/49! Years full of historical interest for sure.

Glad to have a Faber featured in the month – though I’m not sure I’m up to plague reading at the moment!

I just requested a reading copy of this one from my rep – can’t wait for it to turn up.

I’m not sure I want to read a plague novel at the moment, but the hurdy gurdy player got me addicted, thanks!

I don’t know, the last quote sounds like a few pubs I’ve been in.

😂