At the start of #ReadIndies month I found myself in plague-ridden C14th century England. My final review for the event takes me back to that century although I now find myself in C14th China which has troubles of it own.

It is a time of political turmoil, one in which the Mongol Empire lost its hold with the Mongolid Yuan dynasty seceding to the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368) but only after the Chinese warlords have battled each other for decades to determine succession. Countryside and towns are devastated and destroyed as bandit bands attack and pillage, and those who wish only to live in peace have to manoeuvre between the rival factions to avoid extermination.

We know the narrator hasn’t quite managed it. The novel opens with him sitting in prison awaiting trial for visiting the art collection of Hu Weiyong, Emperor Taizu’s disgraced prime minister. This is enough to link him to Weiyong’s conspiracy. It seems the Chinese have swapped a fair administration by a foreign power for a home-grown dictatorship. The maxim better the devil you know is established by the narrator’s memories documented in the papers we are supposedly reading,

He is Wang Meng, who was happy to work as a minor official in the Mongolid adminstration. Better to work for a good administration than for a corrupt one, he believes, although at one point he mulls on whether this constitutes treason. His real passion is painting, and although not recognised during his lifetime, he is now celebrated as one of the 4 great masters of the Yuan dynasty. All he wants to do is paint, but, because a) he is descended from a previous emperor and b) he is a talented administrator and war strategist, life – or rather the bandits and warlords – continue to demand his services. He continually finds himself balancing on a tightrope … serving those he must without falling foul of the other side.

For an artist who wishes only to contemplate the 10,000 things of nature and capture them in his exquisite paintings, he witnesses some high drama: sieges, battles, mass executions. Conversely there are the peaceful moments in which he is free to wander the countryside, admire the waterfalls and mountains, and develop his painting style. (Much to the chagrin of his wife, who is frustrated by his lack of ambition.) On one of his journeys he meets a certain Ni Zan. Theirs is a friendship with an inauspicious start but one of the most influential for his artistic development. Ni Zan also becomes one of the 4 masters of the Yuan Dynasty.

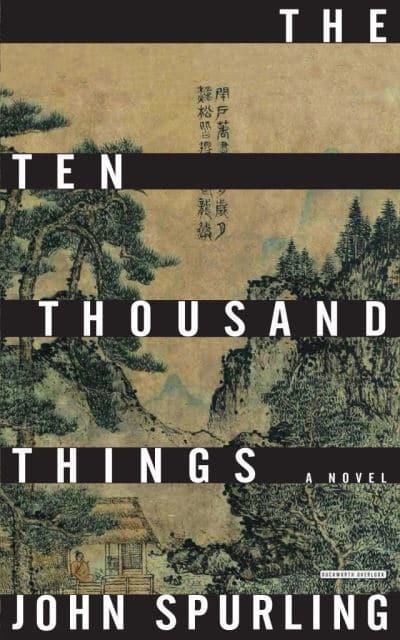

Wang Meng’s fictional memories are full of contrasts: the brutality of war, the philosophical considerations, practice and appreciation of fine art. Spurling’s prose is as detailed and exquisite as the paintings of his subject (see the book jacket which features Wang Meng’s Writing Books under the Pine Trees) and the novel is best enjoyed at a measured pace. (Too much detail would be lost if racing through it.)

I heard that The Ten Thousand Things was rejected by at least a dozen publishers before Duckworth, who pride themselves on their “passion for compelling, impeccably researched historical fiction”, took it on. Theirs was a good call as Spurling’s novel went on to win the 2014 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction.

Founded in 1898, Duckworth is one of Britain’s oldest publishers still under independent ownership. I strongly recommend you check out their history for an insight into how an independent publisher survived the trials and tribulations of the C20th century.

This book sounds exciting, with the narrator wanting only to paint and being caught up in history.