I can never forget the scene in Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief when Death moutns for the human race, for the horrors it faces, the evil it inflicts upon itself. Isn’t that sentiment reflected in Lachnit’s painting? In the midst of the firestorm, death is grieving, weeping with the mother. The child is looking on, not fully comprehending the hell that surrounds him.

Alexander Kluge was 13 when the Allies bombed his hometown to smithereens just 1 month before the end of the war. (8.4.1945). Halberstadt in Saxony-Anhalt was unfortunate enough to be on the reserve target list on the day the primary target had too much cloud cover. The airraids sirens sounded. A scant half-hour later, 550 tonnes of bombs had been released in 6 waves, and the civilian population was fighting for its life in the cellars beneath the houses, on the streets reduced to bubbling tar, trying not to get sucked into the firestorm itself.

The first section of Air Raid describes the event and its aftermath from the civilian viewpoint. Horrific, but not without its absurdities: the cinema attendant who, following the first wave of bombing, thinks she can tidy up the place for the afternoon showing, two aircraft observers on the church tower all kitted out for a picnic with their “folding chairs, torches, beer, packets of bread, binoculars and walkie-talkies”. Following the attack, a local photographer capturing images of the destruction is arrested for spying. (Those photographs are included in the book.) Absurdity aside, this is overwhelmingly a human tragedy. Without a strategy there is no way of surviving as Gerda Baethe realises as she tries to work out how best to protect herself and her three young children with her own limited resources.

At which point Kluge switches to the military, their vast resources and their viewpoint: the rationale behind the saturation bombing of the Allies and the clinical execution of the strategy. This was the most chilling section of the book for me. The sheer callousness of first bombing the escape routes from the town so that civilians could not escape. How we as a species can do this to one another is beyond me. But we do, time and time and time again as Kluge shows in the third section which includes 17 other stories about the air war primarily in other parts of Germany. He recounts acts of brave volunteers, reports on the behaviour of zoo animals during airraids, and even the case of sand-weeping cathedrals in the Rhineland.

Kluge includes more recent cases of man’s inhumanity to man to bring his report right up to date. I found the detail concerning the lack of on-site expertise following the attack on The Twin Towers astounding. But then who would ever have thought a disaster recovery plan of such a scale to be necessary?

I’m tempted to say that there’s no sugar-coating in Kluge’s book, yet I’m sure he has omitted more harrowing images and experiences. Even so, this is the reality of war and Air Raid is rightly called a touchstone event in post-war German literature.

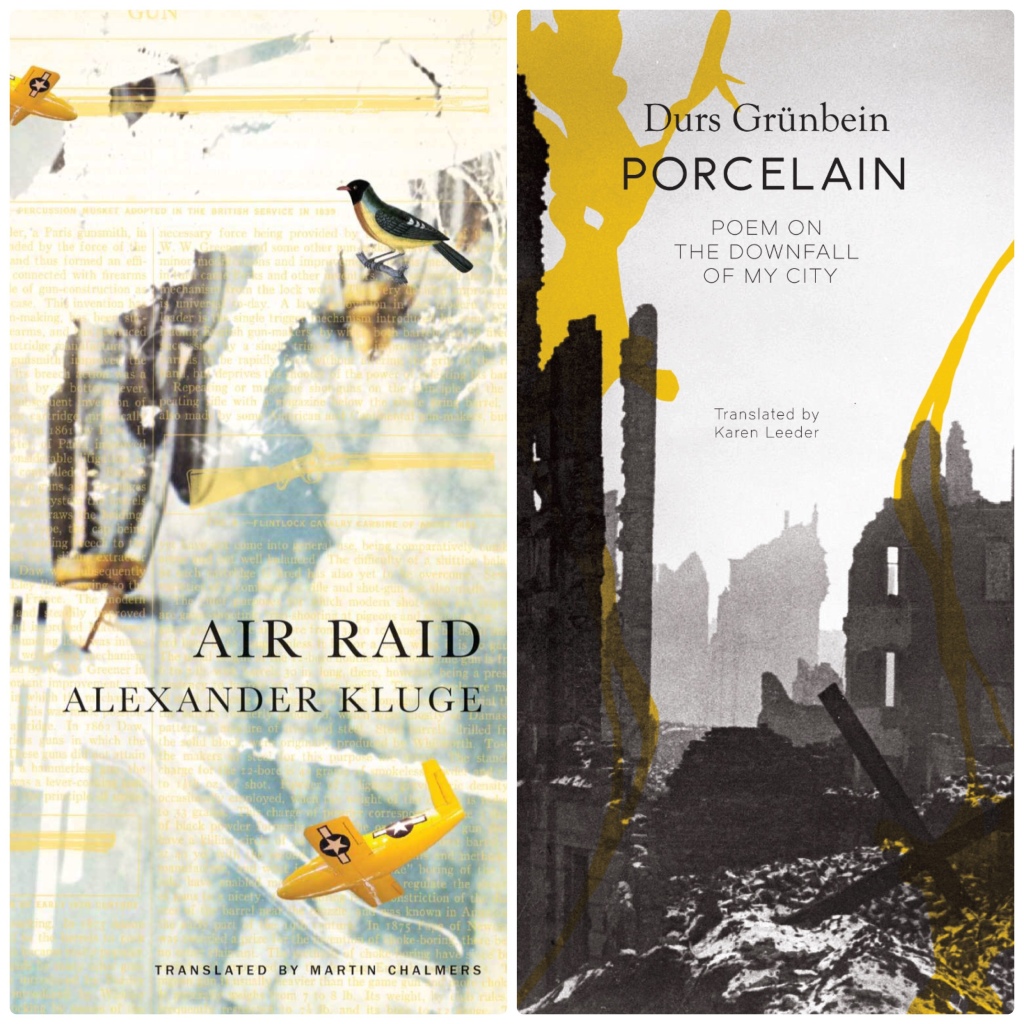

Durs Grünbein’s book-length poem, Porcelain, must surely be another. From 1992 to 2004 (the year the Frauenkirche restoration was completed) Grünbein sat down and composed a canto on the anniversary of the Dresden bombing. These he collected and supplemented for publication as a single cycle of poems, and he has now added a 50th canto to mark the 75th anniversary of the catastrophe/atrocity/war crime? The English translation by Karen Leeder is due for imminent publication.

Judging from the translator’s foreword this poem has generated much controversy, Firstly there are those who feel that Grünbein, who was born 17 years after the bombing, has no right to write about it. Personally I wouldn’t question the right of a son of Dresden, who grew up in the war-shattered city (the Frauenkirche restoration wasn’t completed until he was 42 years of age), to do exactly that. Secondly there’s the question of distance. Grünbein doesn’t buy into the whole victim-narrative, the story that Dresden was entirely innocent. Did not her cooperation with the Nazi regime set her up for some kind of retribution? There’s a rather provocative image of Dresden, like Esau (Genesis 25) selling out her birthright for a bowl of lentil stew. (canto 10.)

Which is not to say that Grünbein does not lament the fate of his hometown. But he is even handed. He reminds his readers that the Allies didn’t design carpet bombing . The Nazis attacked Guernica and Coventry long before.

There are so many tones and viewpoints in these poems, where to begin? With the anticipation of his critics in canto 1. With the city in the sights of the bombers in canto 2. A bird’s-eye view of the city from the top of the the golden statue of August the Strong. Or even the view of the iconic angel overlooking the ruined city.

There are images in common with Kluge. Bubbling tar, the smashing of crockery. In Kluge beer mugs, in Grünbein the Meissen porcelain which gave Dresden her wealth and his poem its name. Altogether finer, in keeping with the classical meter of his poem, which alludes in many places to classical mythology, historical figures and the glories of Dresden’s past. But there is a dissonance – like its porcelain, Dresden was shattered during the raids of 13-15 February 1945. The city has been put back together in the years since, but it’s not quite as it was. This is reflected in the poems. The classical form is disrupted with half-rhymes, breaks in the metre, both in the German original and Leeder’s English translation. As is the informal, almost irreverent language, that is used again and again. I mean when was the word “gob-smacked” ever used in classical poetry? It’s hard to maintain classical and intellectual discipline when you’re coming to terms with devastation on this scale.

Air raid – Alexander Kluge (1977) Translated by Martin Chalmers (2014) / Porcelain – Durs Grünbein (2005) Translated by Karen Leeder (2020) / Both published by Seagull Books

As a native of Coventry, I share Grünbein’s doubts as to his city’s complete innocence (the eightieth anniversary of the destruction of the old cathedral was last Saturday…).

Both of these sound so powerful, Lizzy. It’s hard to think that anyone was innocent during that conflict, apart from the civilians who are usually the ones who suffer the most….

Thanks for these reviews Lizzy- I didn’t know of either book before and both seem relevant to the question of how subsequent generations respond to/ discuss catastrophic historical events. And that photo of Dresden never fails to shock -as did the contemporary footage shown in the recent BBC4 documentary Berlin 45.

Great post! I had not heard of those 2 books. It reminds me of Vonnegut’s slaughterhouse 5, and of Sebald’s Natural History of Destruction

There’s a section of said Sebald included as an epilogue in the Kluge volume …