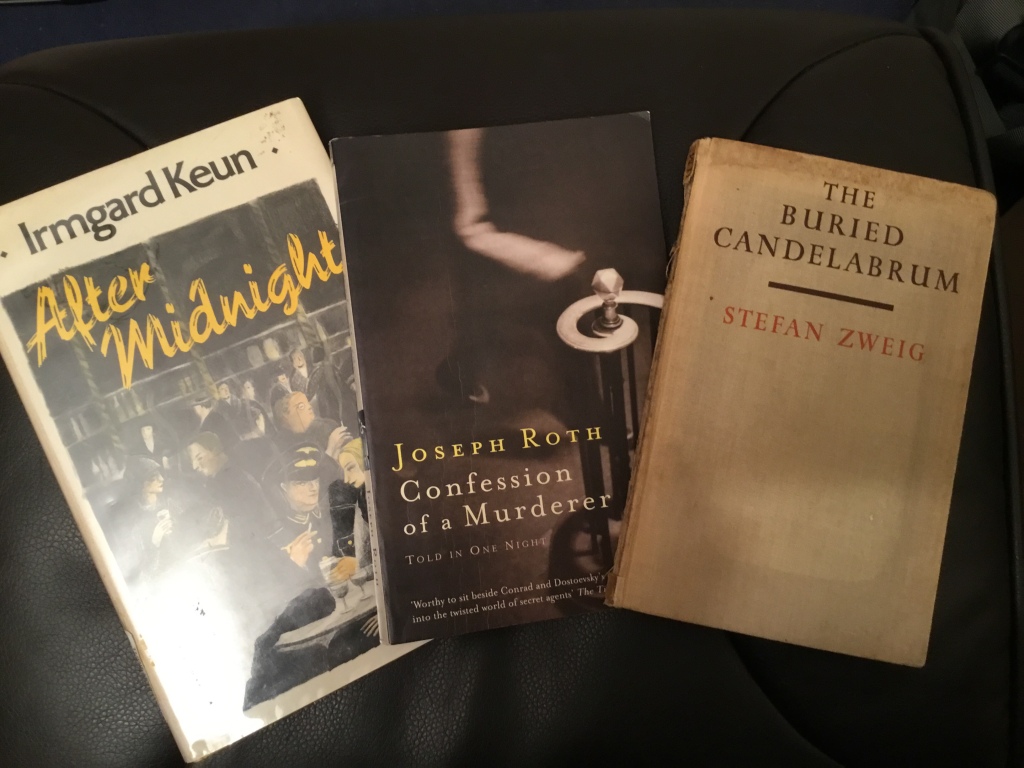

You all know how easy it is to draw up a reading plan … and then never follow through. Well it was January 2016 when I decided that I wanted to read these three works together to compare and contrast.

How so? Because these were the novels that Keun, Roth and Zweig wrote in the summer of 1936 while they were staying in Ostend, having fled from the Nazi regime. And it was Volker Weidermann’s Summer before the Dark that gave me the idea. (BTW I still stand by my gushing review.) As for compare and contrast, it will be more of the latter, because they are all very different.

So almost six years after the plan was formed, here we go. Ladies first …

After Midnight – Irmgard Keun (Published 1937)

Translated from German by Anthea Bell

The setting of Nazi Frankfurt am Main gave me quite a jolt, because these are the squares, streets and cafés of my former abode, where I spent the carefree days of my 20s in a relatively carefree city. How utterly different the atmosphere during the early years of the Third Reich. Before the novel has begun 19-year old Sanna has fled Cologne, after having been unjustly denounced to the Nazis by her aunt. She is now staying with her brother and his wife; Algin is a successful writer, though struggling to get his new work past the Nazi censors, Saska is suffering from an unreciprocated passion for Heini, a man with a Jewish background. Sanna’s fiancé is back in Cologne, saving to open a business so that they can marry. However, Sanna’s main wish at the start is to be able to enjoy her beer in peace but, with her girlfriend who is dangerously in love with another Jewish man, but that is not possible. “It always used to be so cosy when two girls went to the Ladies together. You powdered your noses, and exchanged rapid but important information about men and love.”

Sanna’s milieu try to maintain their flippancy and their pleasure-seeking, and there are some terrific one-liners. Sanna herself is irreverent towards the Führer, who “spends all time time having his photograph taken”, but having learnt her lesson in Cologne about such heresy, she is very careful about who can hear her. Heini’s one-liners are the most biting: “Female flesh and butchered meat need clever lighting. Good lights are absolutely essential in a butcher’s shop or a nightclub.” Yet much effort is required to maintain a semblance of light-heartedness in a society gone mad. At one point, having met a man who claims to have created a divining rod to detect Jews, Sanna describes her party as “disconsolate as unredeemed pawnbroker’s pledges”. The story darkens into one involving suicide and murder, approaching the point when Sanna and her fiancé, Frank, decide to flee to Rotterdam, on a train which departs after midnight. Knowing what we know now about the fate of Rotterdam when the Nazis invaded Holland some four years after Keun wrote this novel, somehow makes this ending even more heartbreaking.

Confession of A Murderer – Joseph Roth (Published 1936)

Translated from German by Desmond I Vesey

The only thing that this novella has in common with Roth’s reality at the time of writing is the setting in a bar during after hours drinking! For as we know Roth was spending his life drinking (and carousing) with Irmgard Keun in 1936; his friend and benefactor, Stefan Zweig, desperately trying to stem his excesses. It’s amazing really that he was able to produce such a controlled piece. (Well, as Weidermann reveals Zweig was a bit more successful in bringing Roth’s writing under control than his schnaps consumption.)

But back to the fictional bar, where a self-confessed murderer is about to reveal all.

His confessional reveals the grubby secrets of Czarist Russia: the injustices perpetrated towards the poverty-stricken illegitimate sons of the nobility, the ensuing bitterness of such children (Golubchik himself) and the desire for revenge on the undeserving usurper of the inheritance he feels should be his. This leads to his recruitment into the Czarist secret police. Thereafter, Roth takes us into the twisted world of the secret service, a journey which takes us from Odessa to Paris, during which Golubchik sinks ever deeper into the moral cesspit. As the saying goes, if you play with fire, you will get burned. And in this case, the player, Golubchik, gets played. The results of which finally sear his conscience, leading to the regret that becomes apparent in his confessional.

Interesting how Roth, an Austrian Jew who fled Germany immediately after Hitler became Chancellor, has gone back to the past. James A. Snead of The New York Times wrote, “Roth’s night-story implicitly identifies the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with Golubchik’s private ‘tragedy of banality.” I don’t see that (possibly because I don’t know enough about the Austro-Hungarian Empire) but I can see connections to the Third Reich: secret police, ostracising of the unwelcome, forced transportation of the undesirable (political dissidents, Jews) to the camps and their probable deaths.

The Buried Candelabrum – Stefan Zweig (Published 1937)

Translated from German by Eden and Cedar Paul

This is unlike any Zweig I’ve read before, and the subject matter is most strange for a secular Jew. It is the story of the Menorah, the seven-branched solid gold candelabrum used by Moses in the tabernacle and Solomon in the temple of Jerusalem. First taken to Babylon, when Jerusalem was captured by Nebuchanezzar II. At the end of Zweig’s novella, the candelabrum is buried in an unknown location, as the man who buried it passes away, his secret intact.

At least it now it is safe from gentile hoards and awaits its “resurrection” when Jehovah will restore it to his temple in Jerusalem. At least that is the thinking of Daniel, the last Jew ever to touch the sacred object. As a young child he experienced the sacking of Rome, and tried to save the Menorah being transported to Carthage by the Vandals. As an old man he finds himself on a pilgrimage to Constantinople, following the Menorah after the sacking of Carthage, to make a plea to Emperor Justinian to return it to Jerusalem. But the Emperor has other plans, and Daniel must find a way to thwart him or the Menorah will remain in the hands of gentiles forever.

This is an interesting read if you’re interested in history from the Jewish viewpoint. Zweig documents the pain of the devout with the empathy that is his hallmark. He wasn’t particularly devout (although he never renounced his Jewish faith) but it’s likely that the scorn and derision of the exiled Jews in Roman times chimed with the scorn and derision he and his people were experiencing during Nazi times. Also their eternal wanderings and the desire for a settled homeland. But the writing didn’t come easily to him. Weidermann again reveals that Zweig, who lacked the experience, could only write a key scene of lamentation, once Roth had written a prototype text for him.

What about that ending? Does it signify Zweig’s despair at the situation of the Jews in 1936, that here they were, once more consigned to eternal wandering, or can it be interpreted, that there was still a sliver of hope that the Jews would be returned to their homeland, even if it would require divine intervention to achieve it?

What a great idea to compare those three works – they were certainly influenced by what was happening all around them, but all very different.

You’ve made me want to go back to reread the Volker Weidermann, many thanks.

I was so tempted to do exactly that while writing this post.

How wonderful – I wasn’t aware that these books were all written at the same time, and I *have* read two of them. In fact, the Keun was my first of hers, and I think it’s still my favourite. The Zweig sounds unusual and I don’t think I have it – but will keep an eye out!

Very interesting project–I love that it took you so long, too! That’s so like me! Now you’ve introduced me to three new-to-me authors writing in a fascinating time period I often seek nonfiction on. Thanks!