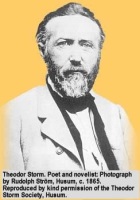

I shall devote the last three days of GLM V to one of my very favourite German authors. It’s a fitting finale also to #novellanov, because Theodor Storm is the master of the C19th novella. Woefully undertranslated into English, although that has changed during the last two decades thanks to the endeavours of one man, Denis Jackson, who recently published a fifth volume of Storm’s novellas (in which I currently luxuriate).

I shall devote the last three days of GLM V to one of my very favourite German authors. It’s a fitting finale also to #novellanov, because Theodor Storm is the master of the C19th novella. Woefully undertranslated into English, although that has changed during the last two decades thanks to the endeavours of one man, Denis Jackson, who recently published a fifth volume of Storm’s novellas (in which I currently luxuriate).

Today I am delighted to welcome Denis to German Literaure Month to find out more about the spell that Storm has cast upon him.

1) How did you become a literary translator?

1) How did you become a literary translator?

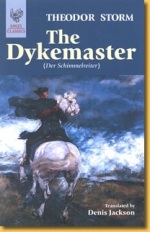

It all began one summer’s evening at a social gathering on the Baltic coast. My host, the headmaster of the Katharineum Gymnasium in Lübeck, read a passage from Theodor Storm’s last Novella Der Schimmelreiter as part of the evening’s entertainment. And as he continued to read, I became aware that I was listening to an author whose prose was like none other I had ever heard; its tautness, linguistic grace and economy were to impress themselves on my mind from that evening on.

‘It was All Saints’ Eve in October. All day a wind had raged from the south-west; in the evening a half-moon stood in

the sky, dark-brown clouds raced across it, and shadows and dim light flew in confusion over marsh and polder; the storm was gathering…….A violent gust of wind came roaring in from the sea, and rider and horse fought their way against it up the narrow path towards the ridge of the dyke. When they were on top, Hauke forcefully reined in his horse. But where was the sea? Where was Jeverssand? Where had the opposite shore gone? – He saw only mountains of water before him which towered up menacingly towards the night sky and in the terrible twilight sought to roll one over the other, and one over the other crashed against the dry land. Crowned with white plumes they rolled in, roaring, as if the cries of every ferocious wild beast in the wilderness were contained within them. The grey stamped the ground with its forehoofs and snorted with its nostrils into the tumult; it felt to the rider that here all mortal power ended; that now the forces of darkness, of death, of nothingness, were about to descend.’

I was unfamiliar with this writer at that time, and inquired into the life and works of the author I had just heard. My host, whose Gymnasium had once been attended by the author in his youth, knew of him in detail, and proceeded to reveal to me not only an unfamiliar author but a world on the west coast of Schleswig-Holstein, North Friesland, that immediately captured my imagination. It was this world, he said, that defined Theodor Storm, his world and his works: I should go there. And I was to go there the following day.

North Friesland is like no other region of earth: its tall dykes, picturesque villages, polder, marsh and heathland not only define its character, but the North Sea Tidal Flats that dominate its coastline, the largest area of mudflats in the world, upon which ‘like dreams lonely islands rest in the mist upon the sea,’ provide the region with a fascination and beauty unique to the eye. When looking out over these tidal flats, from the vantage point of a dyke, one looks out as if into eternity. This was the world of Theodor Storm, into which he was born in 1817 and in which he lived for the major part of his life, whose works were to embody the very nature, culture, and history of this unique region.

Like Storm, I have lived by the sea for the greater part of my life; his thoughts and experiences of its beauties and perils were akin to mine. And as I explored the coastal town of Husum in which he lived, and the heathland and beautiful Frisian villages that became the settings for his prose and lyric verse, I grew to become one with this author. His past life and mine were henceforth to co-exist through the medium of translation.

2) Reading between the lines, Theodor Storm is the only author you want to translate. If true, why is that?

On returning to England I searched in vain for Storm’s works in English – only to discover that he was virtually unknown in this language. The few works that were available, lay out of print and in dust on the shelves of the British Library in London. It was then that I decided to devote my future retirement to translating his works; that his fiction deserved to be far better known to the English-speaking reader. It was to be a significant task that was to extend over the next 23 years – researching, translating and publishing.

Having completed the research and translation of Der Schimmelreiter (The Dykemaster, 1888), the first volume in the future series, I was fortunate to discover a publisher, Angel Books of London, whose objective was the same as mine. It had been looking for a translator of Storm for many years! Together we have published thirteen of Storm’s novellas in English, ten of which into English for the first time. Without such a publisher this series would never have been possible. To have had to search for a publisher for each and every translation would have been out of the question, for I had approached some twenty-five publishers, both in the UK and in America, with my translation of Der Schimmelreiter without success, before discovering Angel Books. Very few editors have studied German and consequently have minimal knowledge of German literature, hence little incentive to publish it: French literature predominates. In addition to this, only some 3% of all fiction published in the UK annually, according to the Translators Association, is in translation, in comparison with some 48% in Germany. The literary translator’s task in the UK is therefore a difficult one.

3) How did you choose which of Storm’s novellas and stories to translate?

The question of which novella to translate does not admit of a single answer, but above all it is made against a background of an intimate knowledge of the author, his life, his times and of the specific setting. Attention is paid equally to literary criticism and academic appraisal in the choice of a work to be translated. But the translator himself must admire the work, must wish to translate it, and to see it ‘reborn’ in the English language, for it is a lengthy, disciplined task that lies ahead of him, demanding visits to the settings in North Friesland. The weakness with literary criticism is that certain academic ‘schools’ tend to favour the same few novellas with the resultant neglect of the many others. The autor becomes like a composer whose overture is all that is repeatedly played. And publishers, too, follow these ‘schools’ for commercial reasons, denying the reading public of choice. Example of this critical bias are Der Schimmelreiter and Aquis submersus, as if these are the only two novellas that Storm ever wrote, although he wrote fifty. Such classics as Pole Poppenspäler (Paul the Puppeteer), Hans und Heinz Kirch, Renate, and Carsten Curator (Carsten the Trustee) to name but a few, are frequently neglected even in their own language.

4) What challenges does Storm present to his translator?

A translator must be able to ‘see’ or ‘experience’ what the author sees or experiences. Storm was to tell the original translator of Immensee (1849) to translate what he meant not what he wrote. To do this one has to ‘see’ and ‘experience’. In Storm’s case, what he saw and experienced in most cases is there to be seen and experienced: a church interior or exterior; a specific view across a marsh or polder; specific places in the town; its harbour; a boat journey across the mudflats to one of the lonely islands; the specific paintings and pond described in Aquis submersus; or to be out alone on a dyke in the biting cold of a winter as I was when translating Der Schimmelreiter. There are scenes in the town and village churches where the protagonist sits in the gallery from which Storm describes the view from it in his ‘economic’ detail. To have sat in these galleries, to have ‘seen’ these views, enables the translator to truly capture what Storm intended – what he ‘means’. There are hundreds of such examples throughout Storm’s works. It must also be borne in mind that readers of today’s classics expect comprehensive notes to accompany the text. Storm was a meticulous researcher and his texts are filled with historical, cultural and social references, a reader’s knowledge of which greatly enhances the narrative.

The value of this ‘seeing’ and ‘experiencing’ is no more visible than in the rendering of Storm’s style: it is taut, concise and economic, the very factors that make him the greatest among Poetic Realists. A good description of it would be: ‘minimalist’. One adjective suffices where many writers would use two; a single short paragraph, even a single sentence, describes a scene or landscape where others would need a page. He is an artist who paints a scene with the fewest brushstrokes possible – it is the reader who ‘paints-in’ the remainder of the picture and its colours. To render this ‘minimalism’ in translation the translator must know precisely what Storm is seeing and describing, for there is no room for textual ‘extensions’.

But no discussion on Storm translation would be complete without mention of Storm’s vocabulary and the challenge it sets the translator. Storm had one of the largest vocabularies in the German language, many words being ‘Storm-created’. It is a nineteenth-century language, sometimes an eighteenth-century one to match the setting of the novella. Over the many years I have been translating Storm, I have needed to collect together a library of nineteenth-century German-English dictionaries, collected during my visits to European capitals. A translator cannot use twentieth-century German-English dictionaries when translating Storm. Even then, one’s own ‘Storm Dictionary’ has to be created as translation problems are solved and archaisms resolved. Today’s data-processing greatly assists the translator by having such dictionaries speedily accessed, but few such facilities exist for these much older dictionaries.

5) How did you differentiate your translations from the ones that came before? Why did you choose to retranslate stories that already had English translations?

Firstly, there is the question of faithfully reproducing Storm’s ‘economic’ style as previously described. Some earlier translations disregarded this vitally important characteristic of Storm’s writing, and in so doing, destroyed all that is essential in Storm.

It was also clear when the translator had never been to North Friesland or to Storm’s coastal town of Husum, for the works involved contained errors that misled the reader. Today’s readerships also expect comprehensive notes, information and introductions to accompany such classics, which cannot be adequately provided without a local knowledge by the translator.

My rendering of Der Schimmelreiter as The Dykemaster, has frequently been questioned – why not, it is asked: ‘The Man on the White Horse’? My response has always been twofold: firstly, as I am later to explain, Storm’s words are chosen as much for their sounds as for their meanings, therefore the title The Dykemaster meets this need, as well as keeping the title’s focus on the central character, the Deichgraf (Dykemaster); and secondly, it avoids a title that in my view is incorrect. There is no such horse in equestrian terms as a ‘white horse’. A white horse is a ‘grey’, a term I use throughout my translations. I am sure that Storm would never have produced a title such as ‘The Man on a White Horse’, as frequently appears in previously published translations of Der Schimmelreiter. In my view it is both contrary to his crisp style of titles over his 50 novellas and to his literary intention.

My rendering of Der Schimmelreiter as The Dykemaster, has frequently been questioned – why not, it is asked: ‘The Man on the White Horse’? My response has always been twofold: firstly, as I am later to explain, Storm’s words are chosen as much for their sounds as for their meanings, therefore the title The Dykemaster meets this need, as well as keeping the title’s focus on the central character, the Deichgraf (Dykemaster); and secondly, it avoids a title that in my view is incorrect. There is no such horse in equestrian terms as a ‘white horse’. A white horse is a ‘grey’, a term I use throughout my translations. I am sure that Storm would never have produced a title such as ‘The Man on a White Horse’, as frequently appears in previously published translations of Der Schimmelreiter. In my view it is both contrary to his crisp style of titles over his 50 novellas and to his literary intention.

6) When do you decide a translation is finished?

After the initial translation, the text is generally laid aside for a month or so, then re-visited to remove the ‘German-English’ elements and to improve the translation, and English, where needed. A translation is consequently never finished; it can always be improved, but an English readership is waiting – and so is a publisher.

7) I assume there was a lot of on-site research. Where did you go and which locations are a must-visit for someone who has yet to make their own Storm pilgrimage.

Storm’s settings that I have visited primarily reside not only in the coastal town of Husum itself, but in the principal villages of Schwabstedt, south of Husum (Renate), Hattstedt, north of Husum (Der Schimmelreiter, Aquis submersus), Drelsdorf, north of Husum (Aquis submersus) and Ostenfeld (Renate) east of Husum. The churches in each of these villages are a must to visit. Not only have they delightful Frisian interiors, but their descriptions occur again and again in one form or another in his novellas. Husum itself is also the home of the Theodor-Storm-Gesellschaft which is a mine of information regarding his life and times. Of all the villages, Schwabstedt is by far the most beautiful; the setting of one of Storm’s finest works, Renate, a story of alleged witchcraft and religious bigotry – a farmhouse there is called Renatehof. But the off-shore islands must not be forgotten and a boat journey from Husum harbour out to one these islands is a journey to remember. It features in Storm’s novella Eine Halligfahrt (Journey to a Hallig, 1871). A ‘Hallig’ is the name given to a small undyked island on the mudflats (Wattenmeer). The sea journey to a Hallig takes you over the legendary village of Rungholt, mentioned in the text of the novella, a small village that was submerged and swept away in the great flood of 1362 and whose church bells can still be heard beneath the waters! The interiors of the farmsteads on these islands are worth many a visit, and are truly characteristic of Frisian life and culture. They feature in many a Storm novella – particularly the dykemaster’s house in Der Schimmelreiter. Frisian longhouses on their high earthworks to protect them from the sea are classic features of the flat landscape.

To be continued. In part two, Denis discusses Storm’s fairy tales, personal favourites from Storm’s oeuvre, and recommends a novella written by someone else!

Fascinating interview. What a lovely scene – “It all began one summer’s evening at a social gathering on the Baltic coast. My host, the headmaster of the Katharineum Gymnasium in Lübeck, read a passage from Theodor Storm’s last Novella Der Schimmelreiter as part of the evening’s entertainment”. Ahh to be there. I’d love to visit North Friesland anyway – such a lovely landscape I’m sure.

Sorry to have missed GLM this year (not the first year I have been too late in catching on to it). I am currently reading Walter Kempowski’s All Or Nothing but won’t be ready to publish anything until the end of next week by which time I will be too late.

You can still join in, Tom. Traditionally, the month ends when I publish the author index – it usually takes me about 10 days to put it together.

Thanks for this interview Lizzy. I’ve only become acquainted with Storm’s work during GLM V and I’ve just finished a second reading of Aquis Submersis – I hope to post something soon. His style is really impressive; I like the description of his style as poetic realism as that seems to capture reasonably well the effect of his writing.

I’ve been looking at all the Angel collections translated by Jackson and I’m sure I’ll have to read much more Storm in the immediate future.

I’ve just read Jackson’s translation of Aquis Submersus myself. I’m not likely to review it though as I wrote about the novella during GLM 1.

Yes, I read your review after my first read. It’s strange but just lately I seem to be re-reading stories that I like quite soon after the first reading.

I started Theodor Storm’s work (the nyrb publication The Rider on the White Horse – aka the Dykemaster – in a translation by James Wright). I am afraid I did not fare to well and wonder if it is the stiffness of the translation or if it just not the book for me right now. I consider it a collection that I will put aside for now, but it joins a selection of books I picked out for GLM that I either did not have time for, or that just failed to hit the spot. My ambition often exceeds my reading speed!

I haven’t read the NYRB translation. If the title’s anything to go by (I fully agree with Jackson the white horse misnomer btw), then there may well be something not quite right about it. Hmmm – there’s an idea for a translation duel …