I wanted to read Christa Wolf’s second novel when it featured as one of the the artefacts in Neil MacGregor’s Germany: Memories of a Nation last year. Published in 1963, two years after the Berlin Wall was built, it brought Wolf political favour, for its explanation of why some people chose to stay in the East.

I wanted to read Christa Wolf’s second novel when it featured as one of the the artefacts in Neil MacGregor’s Germany: Memories of a Nation last year. Published in 1963, two years after the Berlin Wall was built, it brought Wolf political favour, for its explanation of why some people chose to stay in the East.

Actually the novel starts with a traumatic event – the nervous breakdown of a young girl called Rita. The story which follows is Rita’s telling of what led up to that point.

When Rita meets Manfred, she is young, inexperienced, shy and timid. He is 10 years older, an educated man, protective, if also patronising. They move into the attic at his parent’s home, where he occupies himself writing a thesis and she, a trainee teacher, starts a summer job, in a train carriage manufacturing plant. This is where her political education begins. As she learns to respect her comrades, even in the face of some unsavoury workplace politics, her own respect for the ‘new society’ grows. At home with Manfred, who despises his ex-Nazi father, his West-loving and possessive mother, and, once he has been disappointed by them, the socialist values of the East, life is not so comfortable. The day arrives when Manfred’s disaffection is complete and he fails to return from an academic conference in the West. Rita is devastated. As soon as she can, she visits Manfred, with the intention of staying herself. Yet she determines in the course of one day that the West is not for her. She forgoes her lover and returns to the East.

The nervous breakdown that follows show the cost of this act of faith. For act of faith it is. Rita’s memories do not depict an idealistic socialist society. Petty politics and power struggles in the factory, harsh treatment by die-hard Stalinists on those left behind by relatives fleeing to the West show the limitations and potential cruelties of this fledgling society. And yet she chooses what she knows over the limitless freedom of the West, hopeful that this new society will, with her help, become a success. It is a decision that sits well, once she has recovered her health.

Maybe later people will realize that during a long, difficult, threatening and hope-filled historic moment it is the spiritual courage of countless ordinary people that determines the fate of those who are born afterwards.

Set in the summer before and the autumn after the building of the Berlin Wall, these words in the context of the novel give voice to the sincere hopes of those who chose to stay and help build what they hoped would be a better society. (The author included). The novel was controversial on both sides of the Wall. In the West because Manfred, the defector, is shown to be unhappy in his new life. In the East, because of the imperfections alluded to above, Wolf was decried by hardliners as a degenerate.

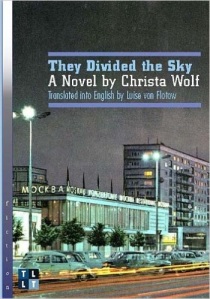

This didn’t stop the East Berlin publishing house, Seven Seas Verlag, turning the novel into a piece of propaganda. In her fascinating introduction, Luise von Flutow, translator of They Divided The Sky, explains the liberties Seven Seas Verlag took with the novel when they first translated it into English in 1965. This included replacing the 1st person narrator with an omniscient, non-critical third, and removing entire sections because they didn’t conform with party discipline. This changes the entire tone and feel of Wolf’s novel. Note well, therefore, if you choose to read Divided Heaven, translated by Joan Becker, you will be reading a novel substantially different to the one Wolf wrote.

This didn’t stop the East Berlin publishing house, Seven Seas Verlag, turning the novel into a piece of propaganda. In her fascinating introduction, Luise von Flutow, translator of They Divided The Sky, explains the liberties Seven Seas Verlag took with the novel when they first translated it into English in 1965. This included replacing the 1st person narrator with an omniscient, non-critical third, and removing entire sections because they didn’t conform with party discipline. This changes the entire tone and feel of Wolf’s novel. Note well, therefore, if you choose to read Divided Heaven, translated by Joan Becker, you will be reading a novel substantially different to the one Wolf wrote.

What a fascinating story about how the publisher drastically changed her book with that first translation.

I can’t believe they chnaged the text like that!

Wow! This is one of Wolf’s I don’t have, and I shall be very careful about the version I choose to read!

Still to read Christa Wolf – I do have A Model Childhood but I’m not going to get to it this week. Fascinating to hear about the problems she had with censorship – but, of course,she was not alone in this!

Love to know what you think of the new translation by Louise von Flotow, They Divided the Sky