Ladies and Gentlemen, We have a ticket to a world premier.

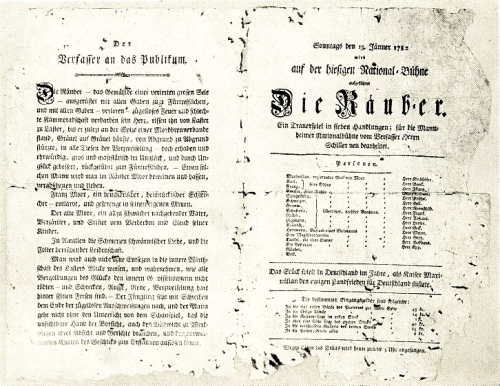

It’s 13.01.1782 and we are headed to the Mannheim Theatre to see the first performance of a debut drama: Friedrich Schiller’s The Robbers. We know this play because we read the text when it was published last year. We are expecting fireworks – metaphorically speaking – for the plot is sensational.

Two brothers are at war – only one, Karl, the older brother doesn’t realise. He has left home to escape the strictures of his position and do his own thing for a while. His younger Machiavellian brother, Franz, is taking advantage of his absence to turn their father against him. Gradually his father’s feelings cool to the point of estrangement and Karl is disowned. This drives him to despair and he joins a robber band, becoming their leader. Franz then makes a play for his brother’s childhood sweetheart, Amalia, and disposes of his father ….

(I’m deliberately not giving specific detail here, because I wouldn’t want to rob you of the shock value. Even now, when I was reading Alexander Fraser Tytler’s 1792 translation in 2015, the plot twists literally took my breathe away.)

Events conspire to bring Karl back to his father’s estate – only, he cannot make himself known for he is a criminal. This cannot end well, nor does it, even if the villain of the piece gets his just desserts. But that is not the end. The final brutal end comes as Karl realises there is no way back to his previous existence and takes extreme measures to shorten the suffering of those he loves.

Storm and stress in spades! Back in 1782, there was an uproar as the play challenged familial loyalties, ducal authority, established notions of criminality and justice. And the young 21-year old author was in the audience to see the effect of his drama. It must have been a heady mix for him, because he was in hot water. He had abandoned his post as regimental doctor in Stuttgart to attend and the Duke of Württemberg will hold him to account. His punishment will be a ban on publishing anything again! Sooner than he knows the young Schiller will emulate Karl Moor and run away (although, thankfully not to a criminal future.)

As mentioned before, The Robbers still retains its power to shock. Overwrought language, heightened emotions, bold depictions of violence prevail throughout. It’s melodrama at its finest. What a villainous creature is that Franz Moor! I love a good villain (by that I mean an evil conniving schemer.) He ticked all the boxes until an out-of-character crisis of conscience. What I can’t stand is a female who is the epitome of virtue without a single flaw. Enter Amalia … Yawn. Still I can’t be too hard on the playwright. At the time of writing, he had been cooped up in an all male military academy for 8 years. What did he known of real femininity? All he could create was a amalgam of the perfect female creatures he had encountered in the literature he had read.

So while The Robbers is not perfect, it certainly brought Schiller to the attention of the literary establishment of the time. What did Goethe, that contemporary giant of German Literature think?

So while The Robbers is not perfect, it certainly brought Schiller to the attention of the literary establishment of the time. What did Goethe, that contemporary giant of German Literature think?

Ich komme aus Italien zurück und finde Dichterwerke im großem Ansehen, die mich äußerst anwidern. Zum Beispiel Die Räuber. Das Rumoren, das sie erregt haben, der Beifall, der gezollt wurde, erschreckt mich. Schiller ist mir verhasst, ein kraftvolles, aber unreifes Talent. (Page 27 Schillers Kritiker – Torsten Unger)

I return from Italy and find some completely repulsive literary works held in high regard. For example The Robbers. The disquiet it has caused, the plaudits it receives, frighten me. I hate Schiller. He’s a powerful but unripe talent. (Translation my own.)

Don’t hold back, Goethe! He changed his mind about Schiller, once he met him, but this assessment of Schiller’s writing capability at the time of The Robbers was spot on.

© Lizzy’s Literary Life 2015

That’s so up to the point, Lizzy – well done!

Great love Goethe comments even then critics could be cutting

Wonderful review, Lizzy! I read ‘The Robbers’ last year and loved it. The ending is definitely quite devastating and must have shocked the audience when the play premiered. Loved Goethe’s comment – “I return from Italy and find some completely repulsive literary works held in high regard.” Made me think of something similar that Tolstoy said of Chekhov’s plays – Tolstoy’s comment was not this strong though. Some of my favourite lines in the play were spoken by Franz – he definitely was a great villain.

Great review, I like a good villain so I’ll keep this work in mind.