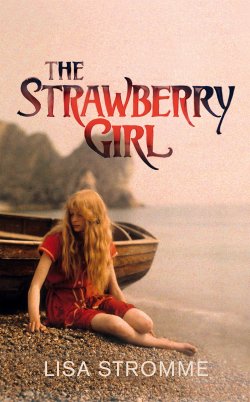

The Strawberry Girl is effectively Lisa Stromme’s ode to the paintings of Edvard Munch. Some twenty are referenced in the text, but the particular focus is the etymology of his most famous, The Scream.

The Strawberry Girl is effectively Lisa Stromme’s ode to the paintings of Edvard Munch. Some twenty are referenced in the text, but the particular focus is the etymology of his most famous, The Scream.

Imagine the alienation, pain, and absolute agony behind it. Now imagine the story that inspired it. The swirl and tumult of tortured emotions, which, according to Stromme’s telling, are unleashed by a passionate yet doomed love affair ….

Asgardstrand, 1893 and the impoverished Munch is renting a simple summer cottage, dividing his time between painting and drinking with his bohemian pals from Kristiania (now Oslo). His reputation is already sullied and none of the locals (whether low or high born) wish to be seen in his company. When Tullik Ihlen, daughter of a wealthy admiral, manoeuvres events to meet him, it is, at first, an act of rebellion against societal constraints. Thereafter, it becomes an all-consuming need – at least on her part. (I’ll return to Munch later.)

Tullik enlists the aid of the maid, Johanne, to watch out for her, cover for her and, at times, enable her assignations with Munch. Tullik insists that Joanne is a friend rather than a servant and because of this Joanne has more dramatic license than you would expect a maid to have. (Except when she points out things Tullik has no wish to hear. Suddenly the hierarchy reasserts itself!) She is the voice of reason, and contains Tullik’s wildest excesses as far as she is able. Tullik’s reputation means more to Joanne than to Tullik, it seems!

Joanne is the strawberry girl of the title. Prior to becoming the Ilhsen’s maid, she used to collect wild fruits from the forest to sell to the summer tourists. She is a budding artist in her own right, and her relationship with Munch (who takes on the role of mentor) provides an interesting contrast to his relationship with Tullik. That too, is a surreptitious relationship – Joanne’s mother would have an apoplectic fit if she discovered it! – but the dialogue between Munch and Joanne is somehow more respectful, and provides insight into what he values in art. When appraising one of Joanne’s paintings, he says:

It’s very good. You are painting what you feel, not what you see. This is the only way to paint.

This comes across in her narrative also. Joanne has synaesthesia, feeling emotions as colours, colours as emotions.

Swirling green. Emerald. Jade.

Exploring. Tentative. Moving. Crawling. A touch of cyan. Opening the prism.

Tullik. Wandering. Hands reaching out. Hands retracting. Away from the sun. Into the unknown.

As much about the creation of Munch’s art – each chapter has a colour or technique for a heading and an epigram extracted from Goethe’s Theory of Colours – as about the doomed affair, The Strawberry Girl also explores social class and mores. Joanne’s upbringing is stricter than Tullik’s for instance, even though it’s the latter who wishes to break free. Thomas’s careful courtship of Joanne contrasts immensely with the irresponsible(?) bohemian abandon of Munch.

Does he love Tullik as much as she loves him? Stromme leaves no doubt as to his sincerity. Tullik became his muse. When the inevitable happened and Tullik’s family put a stop to it, he did suffer, but with his art to fall back on, he was not threatened by the depths of despair depicted in The Scream.

Tullik Ilhsen becomes the living embodiment of the painting when her father forbids her marriage to Munch.

With a gurgling eruption, there was a piercing scream.

It eroded her. Ate her up from the inside. Mouth stretched. Lips taut. Lamenting. Soul ripped clean from her being. Tearing. Snagging on memories on its way out. Gasping and brutal. Her heart was dissected before me. Fragmenting. Splintering. The sound: primal. A force of nature. Unstoppable. Unyielding. Face contorted. Chest concave. Pain searing across her eyes.

I’m not a Munch aficionado but that evocation of The Scream I do recognise, and it gives me confidence that Stromme has authentically transposed other paintings elsewhere. Some references are overt but others I suspect are woven in quite subtly. Wouldn’t it be interesting to sit down with Munch’s portfolio to match the novel’s telling to the twenty paintings listed at the back? I was too absorbed in the story to interrupt myself on first pass.

Final analysis: Not entirely convinced this is the etymology of The Scream but nevertheless a darn good yarn.