Translated from Czech by Alex Zucker

Translated from Czech by Alex Zucker

Experts agree that animals are almost like people.. As long as they’ve got a nice place to live and something to keep them entertained, they can do without freedom … In a good zoo, where they’re well-fed and have a chance to socialize, most animals are happier than they would be … in lonely and dangerous freedom.

That quote neatly summarises the attitude of the Communist regime in 1950’s Soviet-dominated Czechoslovakia. Kovály’s novel demonstrates the impact of such on the citizens of Prague, or more accurately the impact on a microcosm of society, the 2 usherettes and their manager at the Horizon Cinema in Steep Street, who come under the close scrutiny of the security services following the murder of a young child in the projection room.

The ladies all have uncomfortable secrets. At the centre is Helena Nováková, whose husband has been falsely imprisoned on charges of espionage. Guilty by association, fired and spurned by her former publishing colleagues, she is now working at the cinema because it is the only way she can earn a living. The regime cannot, however, accept her innocence, and so begin to track her every movement. The manager is a state informant, tasked to do just this. The second usherette is having an affair with a local police inspector, who, despite having solved the child’s murder, continues to keep a watchful eye on the cinema.

The puzzle of who is who and what they are up to is not easy to piece together – deliberately so, to reflect the realities and paranoias in 1950’s Prague. Chapters often begin with a knock on the door and the entry of an as yet unidentified character. There’s no way of knowing whether the entrant is friend or foe. The culmulative effect of this found me breathing a sigh of relief when it wasn’t state security on the threshold.

In Part I the focus is firmly on Helena, whose experiences draw much from the life of the author herself (explained in the introduction by Kovály’s son). The narrative, often in first person, takes us deep into the thoughts of a lonely, confused woman who wants nothing more than to ease her husband’s predicament. She is convinced by others that the best way to do this is to have an affair with a powerful man, Hrůza, who may be able to help. For his part, Hrůza, who works for State Security, only wants to get closer to her to find evidence of her husband’s guilt (because, of course there is none). He uses their relationship in the most cynical way with tragic consequences. The big question is can Helena be said to have colluded with the State?

Thus ends Part 1 and Part II begins with the actual murder of the title. The victim is Nedoma, the local police inspector, who has infiltrated his way into almost all of the various intrigues. The result is that he knows too much and everyone has motive to kill him. Some more than others. Enter Vendyš, the official in charge of the case, a man with no political agenda, his concern a straight-forward murder investigation. Did I say straight-forward? No chance. Although Vendyš, based on Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, is an ample match for the twists and turns that present themselves in the case, no-one can match the interference from the powers that be.

There are many misdirections in the denouement. Only one character in the whole sordid tale has a crisis of conscience and seeks redemption with a confession that satisfies the needs of the authorities. That this isn’t the whole story is revealed only in the final chapter when two fat men (one fat, one even fatter) converse. Who these men are and what the information is passed onto them in the cinema is never revealed, but there is a delicious irony that, despite the intense levels of surveillance by the authorities, there are times when they can’t see what is right under their noses.

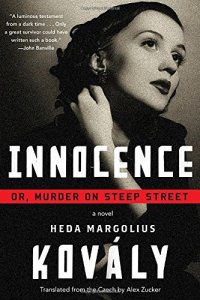

Innocence, or Murder on Steep Street is clever and satisfying. It demands patience, however. There are a lot of characters, many addressed by more than one name. Action is often not on the page, but indirectly observed during conversations. At the heart is an expose of an inhuman and corrupt society but more than that, a hard and depressing lesson that true innocence in such is unsustainable. To quote the epigraph from Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, All things truly wicked start from an innocence.

This sounds wonderful! I’ve put it straight on my wishlist!